– Facts on Fragrance Infographic – click here.

– DOWNLOAD and PRINT Facts on Fragrance Flyer.

What is fragrance?

Fragrance is a term which refers to any substance or mixture of substances intended to convey a scent, or mask an odor. Fragrance can come from both natural sources (plants, flowers, foods) as well as synthetically manufactured fragrances commonly found in scented household products. A manufactured fragrance can be composed of tens to hundreds of individual fragrance chemicals, but it most often simply listed by the generic term “fragrance”.

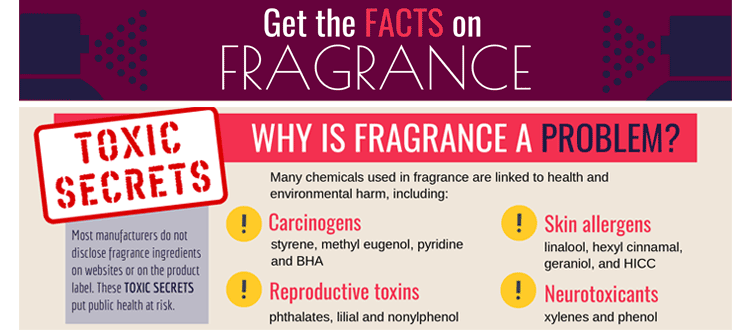

Why is fragrance a problem?

Fragrance can contain undisclosed chemicals of concern which can harm health. There are over 3,000 fragrance ingredients declared by the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) to be currently in use in fragrance.[1] This list includes:

- Carcinogens such as styrene, methyl eugenol, pyridine and BHA,

- Reproductive toxins such as phthalates, lilial and nonylphenol,

- Neurotoxicants such as xylenes and phenol,

- Skin allergens such as linalool, hexyl cinnamal, geraniol, and HICC.

These fragrance ingredients and numerous others have been detected in testing of fragranced household cleaning and personal care products, but the vast majority are not disclosed on the product label.[2][3]

How fragrance can harm our health:

Skin allergies to fragrance are well documented in the scientific literature. Between 2-11% of the general population experience skin allergies to fragrance.[4][5]

Exacerbations of asthma and COPD can be triggered by fragrance exposure.[6][7][8]

Neurological impacts such as migraines have been associated with fragrance.[9][10]

In the U.S. these types of reactions are quite common. In a national survey, over 34% of respondents in the U.S. reported health problems, such as migraine headaches and respiratory difficulties, in response to exposure to fragranced products.[11]

Disproportionate impact:

Women have 2-3 times greater risk of fragrance skin allergies than men.[12][13]

Salon workers are disproportionately exposed to fragrance in the workplace. Hairdressers and beauticians have a 47-fold higher risk of fragrance skin allergies than people in other occupations.[14]

The California Work-Related Asthma Prevention Program has documented that use of fragranced products in the workplace is associated with work-related-asthma.[15]

Massage therapists and geriatric nurses also have higher rates of fragrance contact allergy than those in other professions, likely due to their extensive exposure to fragranced lotions and hand cleansers.[16]

Growing use of fragrance worldwide has led to global environmental contamination by certain fragrance ingredients:

Persistent and bioaccumulative fragrance ingredients such as synthetic musks have been detected in rivers and lakes[17], drinking water[18], sediment[19], air[20], and all kinds of wildlife from fish[21] to birds to harbor seals.[22] Musks are also commonly found in human blood[23], fat tissue[24] and breastmilk.[25]

Fragrance exposure is ubiquitous:

There is ubiquitous use of “fragrance” in household products, such as personal care products and cleaners and data reflect that use of fragrance has been increasing over time. Indeed, for some product categories fragrance-free products can be especially difficult to find. For example, ninety-six percent of shampoos, 98% of conditioners and 97% of hair styling products contain fragrance.[26] Ninety-one percent of antiperspirants, 95% of shaving products, 83% of moisturizers, and 63% of sunscreens contain fragrance.[27][28] Ninety-one percent of lip moisturizers, 71% of lipsticks, 50% of foundations, and 1/3 of all blushes and eyeliners contain fragrance.[29][30] This makes fragrance exposure impossible to completely avoid.

Industry Secrecy Hampers Health and Restricts Consumer Right to Know

Most often, manufacturers of fragranced products do not disclose the individual ingredients that make up their scents. The failure of manufacturers to disclose fragrance ingredient information to their customers, results in many people suffering from unnecessary exposures. Millions of people are affected by fragrance, suffering rashes or breathing problems unnecessarily with limited ability to prevent or avoid their symptoms. Disclosure of fragrance ingredients in household products could alleviate this problem significantly by giving patients and their doctors the information they need to better identify and avoid exposure to problematic ingredients.

Industry self-regulation leads to inadequate safety assessment, continued use of unsafe ingredients

The safety of fragrance chemicals is not determined, monitored or safe-guarded by any governmental agency globally in any comprehensive fashion. Instead, the fragrance industry has been trusted to self-regulate and to establish its own safety guidelines for the use of fragrance chemicals through the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) and its research arm, the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM). Significant problems with the industry self-regulated safety program include:

- An inherent conflict of interest that arises when an industry self-regulates the very products from which it derives profits.

- The majority of safety studies on fragrance ingredients are unpublished research papers conducted by the major fragrance manufacturers.[31]

- RIFM’s “independent” Expert Panel is handpicked by the industry and reviews safety data on fragrance ingredients that has been fully compiled and curated by RIFM staff.[32]

- IFRA does publish Standards which implement bans and restrictions on over one hundred different fragrance ingredients. However, there are no Standards published for the most controversial and problematic fragrance ingredients. And the Standards are purely voluntary, with little to no compliance verification required.[33]

- IFRA standards establishing “safe” levels of skin sensitizers have largely failed, resulting in no reduction in the prevalence of fragrance sensitization. In some studies, the rates of fragrance allergy have increased in recent decades.[34][35]

Solutions and Recommendations

Support Fragrance-Free Public Spaces

The Amrican Lung Association provides sample fragrance-free policies to submit to your workplace, schools, gyms, etc. Click here to learn more and download policies.

Advocate for Better Regulation

Contact decision-makers to support legislation that require fragrance ingredient disclosure and strict chemical safety screening that puts public health first. Ask WVE’s Director of Programs and Policy, Jamie McConnell, about policies in your area.

Contact Companies Directly

Call customer service numbers and tell companies to disclose all fragrance chemicals and eliminate harmful ingredients.

Educate and Engage Others

Print this flyer to help start a conversation with neighbors, co-workers, or post on a community board. Write an LTE to your local paper on the problems with fragrance safety and disclosure.

Text FRAGRANCE to 52886

And stay updated on ways you can get involved with others in your area to take on toxic fragrance chemicals!

– Facts on Fragrance Infographic – click here.

– DOWNLOAD and PRINT Facts on Fragrance Flyer.

[1] IFRA Transparency List: Available at: http://www.ifraorg.org/en-us/ingredients

[2] Breast Cancer Prevention Partners (2018) Right to Know: Exposing toxic fragrance chemicals in beauty, personal care and cleaning products. September 2018. Available at: https://www.bcpp.org/resource/right-to-know-exposing-toxic-fragrance-chemicals-report/

[3] Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ et al. (2012) Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ Health Perspect; 120: 935–43.

[4] Schnuch, A., Lessmann, H., Geier, J., Frosch, P.J.and Uter, W. (2004) Contact allergy to fragrances: Frequencies of sensitization from 1996 to 2002. Results of the IVDK. Contact Dermatitis. Vol. 50. pp. 65-76. 2004.

[5] Schafer, T., Bohler, E., Ruhdorfer, S., Weigl, L., Wessner, D., Filipiak, B., Wichmann, H.E. and Ring, J. (2001) Epidemiology of contact allergy in adults. Allergy. Vol. 56. pp: 1992-1996. 2001.

[6] Sama SR, Kriebel D, Gore RJ, DeVries R and Rosiello R. (2015) Environmental triggers of COPD symptoms: a cross sectional survey. COPD Research and Practice (2015) 1:12

[7] Ritz, T.R., Steptoe,A., Bobb, C., Harris, A.H., and Edwards, M. (2006) The Asthma Trigger Inventory: validation of a questionnaire for perceived triggers of asthma. Psychosomatic Medicine. Vol. 68. pp: 956-965. 2006.

[8] Kumar, P., Caradonna-Graham, V.M., Gupta, S, Cai, X, Rao, P.N. and Thompson, J. (1995) Inhalation challenge effects of perfume scent strips in patients with asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Vol. 75, pp: 429-433. November 1995.

[9] Peris F, Donoghue S, Torres F, Mian A and Wöber C. (2017) Towards improved migraine management: Determining potential trigger factors in individual patients. Cephalalgia. 2017 Apr;37(5):452-463.

[10] Silva-Neto RP, Peres MP and Valenca MM (2014) Odorant substances that trigger headaches in migraine patients. Cephalgia, Vol. 34 (1) pp 14-21. (2014)

[11] Steinemann A (2016) Fragranced consumer products: exposures and effects from emissions. Air Quality and Atmospheric Health. Volume 9, Issue 8, pp 861–866. December 2016.

[12] Schafer, T., Bohler, E., Ruhdorfer, S., Weigl, L., Wessner, D., Filipiak, B., Wichmann, H.E. and Ring, J. (2001) Epidemiology of contact allergy in adults. Allergy. Vol. 56. pp: 19992-1996. 2001.

[13] Nardelli, A., Carbonez, A., Ottoy, W., Drieghe, J. and Goossens, A. (2008) Frequency of and trends in fragrance allergy over a 15-year period. Contact Dermatitis. Vol. 58: pp: 134-141. 2008.

[14] Montgomery RL, Agius R, Wilkinson SM and Carder M. (2018) UK trends of allergic occupational skin disease attributed to fragrances 1996-2015. Contact Dermatitis. 2018 Jan;78(1):33-40.

[15] Weinberg JL, Flattery J and Harrison R. (2017) Fragrances and work-related asthma–California surveillance data. Journal of Asthma, DOI:10.1080/02770903.2017.1299755

[16] Uter W, Schnuch A, Geier J, Pfahlberg A and Gefeller O. (2001) Association between Occupation and Contact Allergy to the Fragrance Mix: A Multifactorial Analysis of National Surveillance Data. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 58, No. 6, pp. 392-398. June 2001.

[17] Baldwin AK, Corsi SR, DeCicco LA, Lenaker PL, Lutz MA, Sullivan DJ and Richards KD. (2016) Organic contaminants in Great Lakes tributaries: Prevalence and potential aquatic toxicity. Science of the Total Environment. 554-555, 42-52. 2016

[18] Wombacher WD and Hornbuckle KC. (2009) Synthetic Musk Fragrances in a Conventional Drinking Water Treatment Plant with Lime Softening. J Environ Eng (New York). 2009 November 1; 135(11): 1192

[19] Peck AM, Linebaugh EK, and Hornbuckle KC. (2006) Synthetic musk fragrances in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario sediment cores. Environmental Science & Technology. Vol. 40(18):5629-35. September 15, 2006.

[20] Peck AM and Hornbuckle KC (2004) Synthetic musk fragrances in Lake Michigan. Environmental Science & Technology. Vol. 38(2):367-72. January 15, 2004.

[21] Ramirez AJ, et.al. (2009) Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Fish: Results of a National Pilot Study in the United States. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. Vol. 28, No. 12, pp. 2587-2597. 2009.

[22] Kannan K, Reiner JL, Yun SH, Perotta EE, Tao L, Johnson-Restrepo B and Rodan BD. (2005) Polycyclic musk compounds in higher trophic level aquatic organisms and humans from the United States. Chemosphere 61, pp: 693–700. 2005.

[23] Hutter H. et.al. (2009) Synthetic musks in blood of healthy young adults: Relationship to cosmetics use. Science of the Total Environment. Vol. 47, pp: 4821-4825. 2009.

[24] Kannan K, Reiner JL, Yun SH, Perotta EE, Tao L, Johnson-Restrepo B and Rodan BD. (2005) Polycyclic musk compounds in higher trophic level aquatic organisms and humans from the United States. Chemosphere 61, pp: 693–700. 2005.

[25] Reiner JL, Wong CM, Arcaro KF and Kannan K. (2007) Synthetic Musk Fragrances in Human Milk from the United States. Environmental Science and Technology. Vol. 41, No. 11, pp: 3815-3820. 2007

[26] Scheman, A., Jacob, S., Katta, R., Nedorost, S., Warshaw, E., Zirwas, M. and Bhinder, M. (2011) Hair products: Trends and Alternatives: Data from the American Contact Alternatives Group. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. Vol. 4,No. 7. pp: 42-46 July 2011.

[27] Scheman, A., Jacob, S., Katta, R., Nedorost, S., Warshaw, E., Zirwas, M. and Selbo, N. (2011) Miscellaneous Products: Trends and Alternatives in Deodorants, Antiperspirants, Sunblocks, Shaving products, Powders, and Wipes: Data from the American. Contact Alternatives Group. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. Vol. 4,No. 10. pp: 35-39 October 2011.

[28] Zirwas, M.J., Stechschulte, S.A. (2008) Moisturizer Allergy: Diagnosis and Management. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. Vol.1. No. 4. November 2008.

[29] Scheman, A., Jacob, S., Katta, R., Nedorost, S., Warshaw, E., Zirwas, M. and Kruk, A. (2011) Lip and Dental Care Prodcuts: Trends and Alternatives: Data from the American Contact Alternatives Group. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. Vol. 4,No. 9. pp: 50-53 September 2011.

[30] Scheman, A., Jacob, S., Katta, R., Nedorost, S., Warshaw, E., Zirwas, M. and Cha, C. (2011) Facial Cosmetics: Trends and Alternatives: Data from the American Contact Alternatives Group. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. Vol. 4,No. 7. pp: 25-30 June 2011.

[31] Women’s Voices for the Earth (2018) Unpacking the Fragrance Industry: Policy Failures, the Trade Secret Myth and Public Health. An investigative report by Women’s Voices for the Earth Published November 2015 Updated September 2018. Available at: https://womensvoices.org/fragrance-ingredients/report-unpacking-the-fragrance-industry/

[32] Women’s Voices for the Earth (2018) Unpacking the Fragrance Industry: Policy Failures, the Trade Secret Myth and Public Health. An investigative report by Women’s Voices for the Earth Published November 2015 Updated September 2018. Available at: https://womensvoices.org/fragrance-ingredients/report-unpacking-the-fragrance-industry/

[33] Women’s Voices for the Earth (2018) Unpacking the Fragrance Industry: Policy Failures, the Trade Secret Myth and Public Health. An investigative report by Women’s Voices for the Earth Published November 2015 Updated September 2018. Available at: https://womensvoices.org/fragrance-ingredients/report-unpacking-the-fragrance-industry/

[34] Montgomery RL, Agius R, Wilkinson SM and Carder M. (2018) UK trends of allergic occupational skin disease attributed to fragrances 1996-2015. Contact Dermatitis. 2018 Jan;78(1):33-40.

[35] Bennike NH, Zachariae C and Johansen JD (2017) Trends in contact allergy to fragrance mix I in consecutive Danish patients with eczema from 1986 to 2015: a cross-sectional study. British Journal of Dermatology Vol. 176, pp: 1035–1041. 2017.